Haag Engineering Co. consultants were called to the set of the feature film Titanic to perform an inspection following collapse of part of the set.

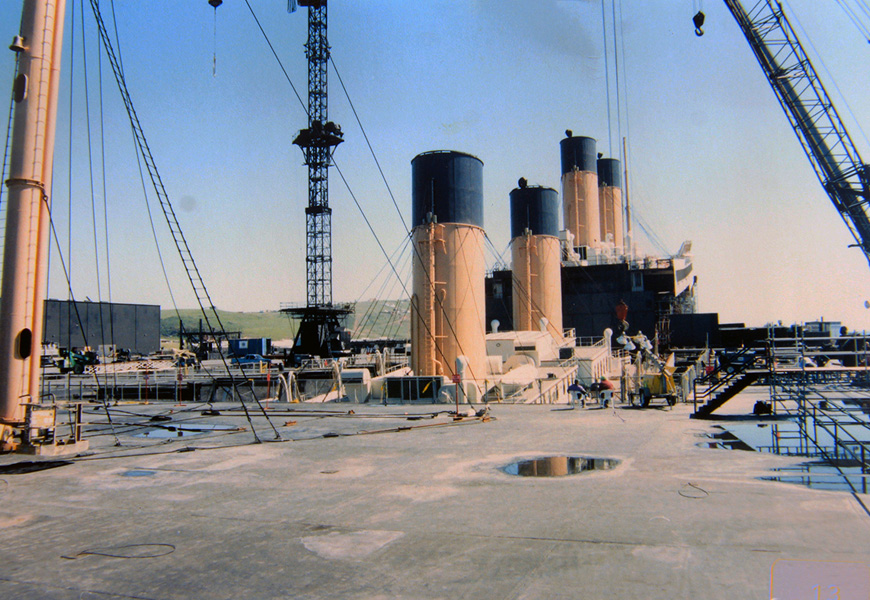

In February 1997, Haag Engineers were called to the movie set of the feature film Titanic. Ironically, the 90% scale movie set “sank” near the end of filming. The overall model was a steel frame mostly on dry land that was clad with metal panels to look like a ship. To simulate sinking, the bow was progressively tilted into a pool of water by lifting the entire frame and cutting the columns shorter. For the final scenes, the bow section was a separate set, supported by a series of hydraulically-actuated cables and buoyant foam blocks to make the set appear to float while it was being actuated with the cables. (The flotation blocks could not support the weight.) Unfortunately, a series of modifications needed to improve realism resulted in support failures that let the set sink, interrupted filming, left expensive actors and crews idle, and impacted actor confidence in the structure.

The set of Titanic was housed in a brand-new movie studio, complete with a 17 million gallon water tank (the largest ever constructed) on the coast of Rosarito, Mexico. When the film Titanic was released on December 19, 1997, it was the most expensive movie ever made, costing about $1 million per minute of screen time, exceeding $200 Million. (IMDB.com)

“The problem with the set, at the time I arrived, was that they weren’t really certain what had occurred. All they knew was that it was suspended on cables and flotation blocks at the time that it partially collapsed,” said David Teasdale, P.E., Haag Principal Engineer and VP of Engineering Services. “We had to wait a day while the tank was drained, and we took that time to learn the structure, review plans, talk to the designers and users, and tour some of the other sets where filming continued. The set had broken and partially sank once earlier, and different groups had different concerns about why. A film production is unique, in that, down days are factored into the film schedule. Therefore, the business interruption claim is not confirmed until filming is complete and it is known that the accident actually cost any time. In this case, the actors and crew were costing many thousands of dollars per day.”

“Once the tank was drained, we observed that one support leg had broken loose, kicked out, and allowed the set of the ship to tilt into the pit of water. In essence, more flotation blocks were called for to improve the buoyant look during filming, and there was only so much room under the set to fit them in. When the extra blocks were added, the cross braces had to be moved higher on the columns. The structural contractor had completed his work and left the site, so he subcontracted a local welding crew to do the work from an engineer’s plan. One main support leg had pulled loose due to a bad weld, and the bad weld was one of many. The solution was pretty simple. First and foremost, the repair needed to be implemented quickly, because time is money, and secondly, since it had failed once before, we needed to restore trust in the set. Therefore, Haag Engineers were included in the repair oversight. Subsequently, we were asked to assist characterizing the failures to help others define whether they met the definitions for insured delays. Haag also testified at the subrogation arbitration.”

A forensic consultant needs to do more than simply identify the problem, and Haag Engineering has a long history of identifying problems large and small, helping with the solution, communicating the information needed to a variety of parties with different interests, and providing the engineering perspective needed for others to resolve any resulting disputes.

by David Teasdale, P.E., Principal Engineer & VP of Engineering Services

David Teasdale specializes in structural evaluations, earthborne and airborne vibrations, geotechnical evaluations, general civil engineering, and wind and related storm effects. He is the primary author and presenter of a Haag classroom seminar course on earthquake damage assessment and Haag’s California Earthquake Adjuster Accreditation course.