Dehumidification Basics

By Thomas Culver, CPAU, IICRC- MRS, WRT, FSRT

As a Senior Consultant for Haag Construction Consulting, I often find myself reviewing a mitigation estimate that has been included in a file to try to gain a better understanding of what the repair scope should look like. Many of these estimates appear to include an excessive amount of dehumidification equipment based on IICRC recommendations. While there may be loss specific circumstances that support an increase in the amount of equipment required, as a field inspector or desk reviewer, do you have a good understanding of the basic principles that help to determine the amount of dehumidification equipment necessary?

The first variable to consider is the total volume of the room or area in need of drying. This can be as simple as calculating the volume of one room or may involve several rooms. The room(s) may have flat ceilings, or sloped ceilings, in which case you may need to determine the average ceiling height. As a reminder, volume is measured in cubic feet (CF), and the basic formula to determine the total volume of a room is length*width*height (L*W*H). For irregular shaped rooms, you may need to first calculate the total area in square feet (SF), then multiply that by the ceiling height.

The second variable to determine is the class of water loss, which is based on the percentage of the total porous materials that are wet as a result of the loss. For example, a 12’ x 12’ room with 8-foot ceilings would have the following area available, assuming all finish materials are porous:

- 144 SF ceiling.

- 4 walls of 96 SF each.

- 144 SF floor.

- Total of 672 square feet.

If the floors were completely saturated and all four walls were wet two feet up, there would be 240 SF of affected material. When divided by the total of 672 SF, that would result in approximately 35.7% of the total available area affected. The IICRC has defined the classes of water loss as follows:

- Class 1: Less than 5% of the available area is affected.

- Class 2: Between 5% and 40% of the available area is affected.

- Class 3: More than 40% of the available area is affected.

- Class 4: Complex assemblies, low evaporation materials. Also referred to as specialty drying.

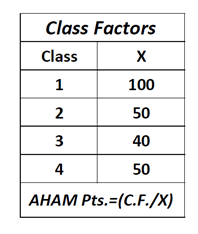

Each class of water loss has been assigned a class factor that will help to determine how many AHAM pints per day are required for effective dehumidification. The AHAM rating is an efficiency rating applied by the Association of Home Appliance Manufacturers, where equipment is tested in a controlled environment of 80 F and 60% relative humidity. The following chart shows the class factor (X) to be applied based on the determination of the class of water loss.

The formula for determining total required AHAM pints is on the bottom of the class factor chart. Once we have determined the total CF of the drying chamber and the class factor of the loss, we can calculate the total AHAM pints necessary for proper dehumidification of the drying chamber.

If we have a drying chamber of 496 SF with 9-foot ceilings, we will first need to determine the volume of the chamber. 496*9 = 4,464 CF.

If the loss has been classified as a class 2 water loss, we can determine the total AHAM pints needed using the formula above. 4,464/50 = 89.28 AHAM Pints.

Most commercial dehumidifiers publish their efficiency rating in AHAM pints and estimating platforms classify dehumidifier size based on a range of AHAM rating. For example, Xactimate classifies a large dehumidifier as being AHAM certified for 70-109 pints per day. The dehumidifier necessary for the example above would be a large dehumidifier based on AHAM pints.

There is also a consideration needed for total air exchanges per hour. The IICRC recommends three air exchanges per hour for dehumidifiers during mitigation. To determine this number, we must consider the cubic feet per minute (CFM) rating of the dehumidifier. This calculation is less involved since we already know the total volume of the drying chamber. To determine the CFM rating necessary, we can use the following two step process:

- Volume/60 = CFM (Cubic feet needed per minute for one air exchange per hour.)

- CFM*3= Total CFM needed for recommended three air exchanges per hour.

Using our drying chamber volume from the previous example of 4,464 CF, we would calculate the following:

- 4464/60 = 74.4 CFM

- 4*3 = 223.2 CFM for 3 air exchanges per-hour

Most equipment manufacturers publish their AHAM and CFM ratings which makes it possible to determine if the equipment being utilized during a mitigation project is appropriate for the drying chamber.

As a field inspector or desk reviewer, there are many different situations and scenarios you may encounter, even in a single day. While you likely have a good grasp of the technical knowledge necessary for most of the files you review, everyone comes across a file or situation at some point that is unfamiliar to them. Whether you need a refresher on a subject you don’t encounter on a regular basis or would like to gain more knowledge about a topic that your knowledge is limited, Haag Education may be a great resource!

Thomas Culver, CPAU, IICRC- MRS, WRT, FSRT is an experienced Senior Construction Consultant, with more than 20 years in the construction and insurance restoration industries. In addition to WRT and FSRT certifications, Mr. Culver has obtained the IICRC Mold Removal Specialist (MRS) certification, which is the highest level of certification that IICRC offers for mold. Mr. Culver is also an ITC certified thermographer and Part 107 drone pilot. Mr. Culver and Haag Construction Consulting offers expert witness services, written report of findings following a site inspection or review of file documents, and comparative reports and estimates for mold remediation, water mitigation, and repair files for residential and commercial losses.

Mr. Culver is proficient in Matterport, Xactimate, Moisture Mapper, T&M Pro and Xactanalysis Claims Management. His areas of expertise includes construction, restoration, mitigation, remediation, clerk of works, and litigation support. TCulver@HaagGlobal.com

Any opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of Haag Engineering Co., Haag Construction Consulting, Haag Education, or parent company, Haag Global, Inc.

Basic forensic techniques when inspecting for hail-related damages to roof surfaces typically include the method of performing a “test square.” This method was developed by Haag engineers in the 1960s and is a widely accepted practice to this day and industry standard. (For more information on the history and methodology, see

Basic forensic techniques when inspecting for hail-related damages to roof surfaces typically include the method of performing a “test square.” This method was developed by Haag engineers in the 1960s and is a widely accepted practice to this day and industry standard. (For more information on the history and methodology, see