Diagnosing Cracks in Common Construction Materials

By Amber Prom, P.E., Director of Curriculum

Identifying damage, especially when that damage has been pointed out to you, is not rocket science. Determining what caused that condition and whether that condition is a concern is a whole other story. Many times, we find ourselves out on site looking at a crack in a material and wondering, what on earth might have caused this? Has the crack been there for some time, or did it develop recently? Is this crack even a concern? While determining the cause and severity of a crack can be somewhat difficult, arming ourselves with information regarding the most common mechanisms that cause cracks to form in our most predominant building materials can help us narrow down the possibilities.

Common Crack Mechanisms in Drywall

While unsightly, drywall cracks are typically harmless. Drywall is not commonly used as a structural material, so there is little worry that any sort of structural harm has been caused by a drywall crack. Drywall is not part of the exterior building envelope, so there is little concern that the crack will let in moisture/weather. However, drywall cracks can be an indicator of a larger problem. Two of the most common causes for drywall cracks are:

- Expansion/contraction of the framing members upon which the drywall is attached (not such a tragic thing) and

- Localized foundation movement ( can be a major issue).

Expansion/contraction is a common phenomenon in wood particularly. Wood is a hygroscopic material, meaning it has a tendency to absorb moisture from the air. When this happens, wood will expand in size. Drywall, on the other hand, does not expand/contract at the same rate as wood, nor is it as flexible a material. This means when the two materials are connected and the wood changes size, the drywall cracks. Most commonly these cracks will show up where the drywall is weakest, which is at the joints between drywall panels. As such, this results in very linear cracks that propagate either vertically or horizontally (See the upper-right image).

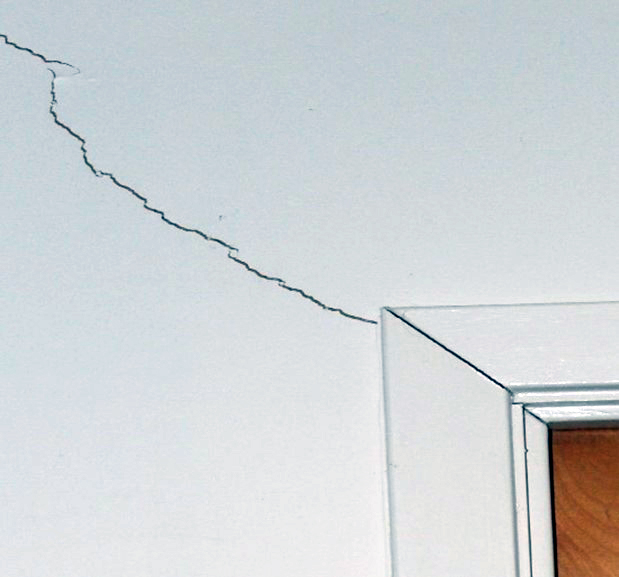

What we need to watch out for though, are cracks that are a result of foundation movement, as that is a larger problem that can cause far more damage than just cracks to finishes. Drywall cracks that are the result of localized foundation movement very commonly propagate either vertically or diagonally from the corners of doors and windows (see the lower-right image), and the cracks are typically concentrated in the area of localized foundation movement, which will need to be verified by a forensic expert. Other indicators of foundation movement are windows and doors that no longer open/close correctly and floor surfaces that do not feel level.

Common Crack Mechanisms in Concrete

Even more common than cracks in drywall are cracks in concrete. Concrete is a brittle material known to perform well in compression but poorly in tension. For this reason, we reinforce concrete with steel rebar to give the concrete member better tensile strength, but regardless, it is exceedingly difficult to altogether prevent concrete from cracking.

The most common cracks you will typically see in concrete are shrinkage cracks. These cracks form when the concrete cures, losing its water content and consequently shrinking in size. This shrinking can cause multi-directional cracks to form in the surface of the concrete, especially if the concrete cures too quickly or cures unevenly. Shrinkage cracks do not typically penetrate the full thickness of the concrete. Instead, they tend to meander in various directions across the exposed surface of the concrete and occur in higher concentrations near the perimeter edges and corners of the concrete member.

Other common mechanisms that can cause concrete to crack include, but are not limited to:

- Issues with post-tensioning practices

- Slab geometry issues

- Differential expansion/contraction stresses

- Differential movement of supporting soils

- Overstressing

- Impact damage

Old vs New Cracks

In addition to working to determine the cause of a crack, we are sometimes faced with determining when a crack developed. Is the cracking something that occurred recently, or did this crack develop sometime in the past? Characteristics that can assist in determining whether a crack is new or old are:

- Newly developed cracks are well-defined, with sharp edges and a clean fracture surface.

- Newly exposed crack surfaces are commonly brighter in color than the surrounding material.

- Older cracks typically exhibit weathered/rounded edges, and their fracture surfaces are often stained, or grime covered.

- New cracks often contain bits and pieces of the fractured material in and around the crack.

- Older cracks often contain debris, grime, algae, cobwebs, paint, sealant, etc., within their confines.

Regardless of the situation, analyzing the cause, severity, and age of cracks can be difficult and arming yourself with as much information about the common mechanisms that can cause these cracks will only make things easier on you. If you find yourself wanting to learn more, Haag Education offers an online course titled “Identifying Distress vs Sudden Damage in Construction Materials.” This course will walk the learner through many of the common reasons our most predominant building materials, like concrete, masonry, drywall, and wood, tend to crack or show distress. The course goes further and covers common causes for nail pops, brick veneer detachment, and various moisture conditions. This course is also part of Haag’s new Haag Certified Reviewer Program (HCR). To register for this course as a standalone, or for more information on the HCR Program, visit www.HaagEducation.com.

Author

Amber M. Prom, P.E., Director of Curriculum

Amber M. Prom, P.E., is Haag’s Director of Curriculum and is based out of the greater Denver area. Ms. Prom is a Registered Professional Civil/Structural Engineer with 18 years’ experience in structural design, project management, forensic engineering, and engineering management/training. Ms. Prom previously worked in the field of forensics as a Professional Development Manager and Principal Consultant for approximately 10 years. As a Professional Development Manager, she was responsible for training all newly hired Civil/Structural Engineers and Building Consultants and providing continuing education/training for existing experts. As a Project Engineer/Principal Consultant, she conducted forensic engineering investigations related to structures which had failed, become damaged, did not operate/function as intended, or were constructed deficiently. Most of her investigations involved hail damage to structures caused by wind, hail, tornados, hurricanes, and earthquakes, along with fires, explosions, ground vibrations, and construction defects. Ms. Prom has also been engaged as an expert witness in numerous mediations, arbitrations, depositions, and trials throughout her career. Currently, Ms. Prom acts as Haag’s Director of Curriculum and develops/manages all of Haag Education’s training curriculum, including the Haag Certified Inspector and Haag Certified Reviewer Programs.

Any opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of Haag Technical Services, Haag Engineering Co., Haag Education, or parent company, Haag Global, Inc.