VISUALIZING THE UNSEEN: MODERN PREMISES LIABILITY ANALYSIS

Christopher DeSantis, RA, AIA, CXLT and Benjamin T. Irwin, PE, DFE, CXLT

At its core, forensic architecture and forensic engineering can simply be thought of as the application of facts and science in answering technical questions posed by a lay audience. Similarly, premises liability evaluation can simply be thought of as a technical evaluation of the interactions between human beings and the constructed environment around them, in response to a specific incident where a specific constructed condition is alleged to have caused injury to a specific person. Seems simple, right?

- Step 1: Analyze the facts.

- Step 2: Apply the science(s) to the facts.

Traditionally, premises liability analysis has focused largely on compliance of the constructed conditions with codes and industry norms. Again, simple right?

- Step 1: Determine the applicable codes and industry norms.

- Step 2: Evaluate compliance of the constructed conditions.

But what happens when the facts are unclear, or even partially contradictory? What if the facts are unknown? Similarly, how do you analyze compliance, if you can’t determine the age of the constructed conditions? These answers require a more modern, multi-faceted, and multi-disciplinary approach.

We can start with a simple idea:

Nearly everything leaves evidence somewhere, and there are many more opportunities to technically investigate a given fact pattern now than there have ever been before.

This is modern premises liability analysis, where the key is to reconstruct a given incident to the greatest extent possible, either physically in reality, in a virtual manner, or in some combination of the two. When an incident can be better visualized, even if the conditions have since changed, it can become much simpler to see the facts, codes, standards, and science more clearly.

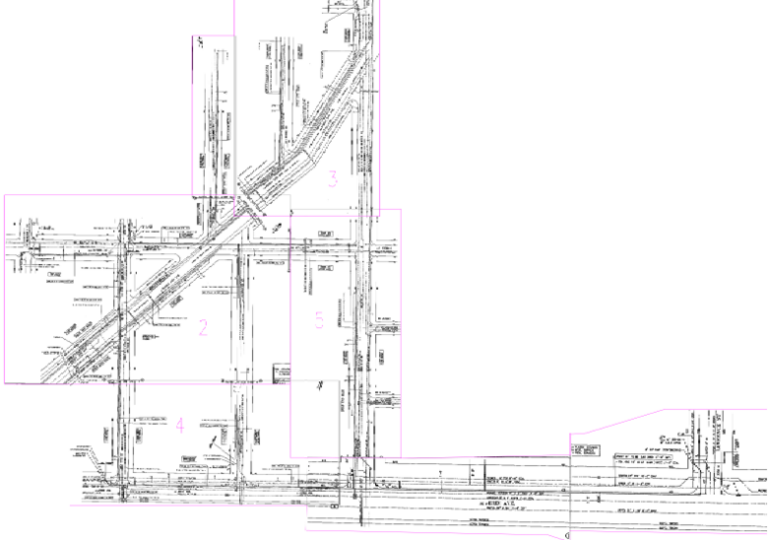

Consider being faced with a fact pattern involving a fall event on a roadway construction site, where the construction site is long gone. There were no witnesses to the incident, limited photos from the time of the incident, and the available testimony created a he-said, she-said situation that didn’t seem to make sense in the context of the other available information. A new first step is needed, to verify the facts before analyzing them.

As a part of this fact pattern, construction staging plans were provided piecemeal and in an incomplete manner, along with out-of-sequence and partially missing/redundant daily field logs. Re-assembling these jigsaw pieces, revealed verifiable extents of the construction zone on the date of the incident, including what construction equipment was on site at the time of the incident. It also revealed the adjacent streets on which the same contractor had performed similar work.

While the dated street level imagery did not indicate the exact conditions present within the construction zone at the time of the incident, it did indicate the construction zone protection methods utilized by the contractor elsewhere on the same project on the adjacent streets. A repetitive pattern of construction zone protection emerged that aligned with only one portion of the testimony, but not the other. Certain elements of the same repetitive pattern were also evident in the limited photos taken from the time of the incident.

The dated street level imagery near the construction zone showed limited construction equipment, surrounded by limited construction zone protection, which more closely aligned with the contradictory testimony, but was actually from a different point in time. Combining all of this evidence using a multi-faceted approach, the conditions actually present at the time of the incident were reconstructed, such that these unseen conditions could be visualized clearly utilizing verifiable facts.

It is not always this complicated, though. Sometimes, a simple review and enhancement of the video surveillance footage from an incident will provide the fact verification needed. There are also now some interior street level images being recorded inside of buildings. Both of these modern technologies can also be used as part of a multi-disciplinary premises liability evaluation approach, revealing details that could not be easily seen before.

Consider another example, one where the video surveillance footage brought confusion, rather than clarity. This basic fact pattern suggested that the wrong incident location was investigated by a property owner after an incident had occurred at a known location somewhere else. The video surveillance footage captured the incident in a verifiable location, as well as the investigation conducted at that same location, but the car shown in the photos from the investigation didn’t match the car allegedly present at the time of the incident. So, what created this discrepancy?

The key to understanding what happened was to visualize the conditions present at the different points in time, as viewed from the perspectives of the different parties at those different times. Some constructed environments are dynamic in nature, with conditions that change frequently. Combining review and enhancement from all of the video surveillance footage (not just the two segments referenced earlier), with review of the designed site features, in combination with in-field measurements, along with analysis of the changes in the dynamic environment over time, the conditions present at the time of the incident could again be reconstructed virtually, making the unseen clear to visualize.

In each case, the early preservation of evidence was key. Early engagement of experts can also help to bring clarity to additional unseen, but verifiable, facts early on in the claims and/or litigation processes, improving the potential for early, informed decision-making. The evidence is often out there somewhere, and our task, together, is to locate, verify, and analyze it in a multi-faceted manner, utilizing our arsenal of modern tools.

What can we bring into clearer focus for you?

Authors

Christopher DeSantis is an accomplished and credentialed Architect with a solid career record of innovative and outstanding architectural design. Prior to joining Haag, Christopher worked as an architect, collaborating with structural engineers in design and preparation of project details, wall sections, and construction documents. He conducted detailed forensic investigations and structural integrity inspections, documented in field reports, in addition to performing contract administration and working as project manager for multiple projects. He also worked as a Graduate Teaching Assistant, an intern/builder at SouthCoast DesignBuild, and as a construction laborer and mason. His project experience includes investigation and restoration of multiple school campuses and commercial buildings. He has designed many large condominium projects, multi-use developments, government buildings, retail and restaurants, and commercial buildings.

Benjamin T. Irwin is a Forensic Engineer with Haag Engineering Co. With dual degrees in architecture and civil engineering from Lehigh University, and over 20 years of diverse professional experience, Mr. Irwin provides a wide array of engineering, design, construction, and safety consulting and expert witness litigation support services. He is a registered Professional Engineer (P.E.) in 23 jurisdictions and is recognized as a Model Law Engineer (MLE) by the National Council of Examiners for Engineering and Surveying (NCEES). He is also a Board-certified Senior Member of the National Academy of Forensic Engineers (NAFE), holding the designation of Diplomate Forensic Engineer (DFE). He had been qualified for, and testified within, local, state and Federal courts, with retentions from both plaintiffs and defendants.

Any opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of Haag Technical Services, Haag Engineering Co., Haag Education, or parent company, Haag Global, Inc.