Storm Reports: Where do they come from (Part 1)

To reconstruct a weather event, a forensic meteorologist searches through numerous databases looking for as much ground truth as possible. One source of ground truth is the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) Storm Events Database which provides the official record for storm reports.

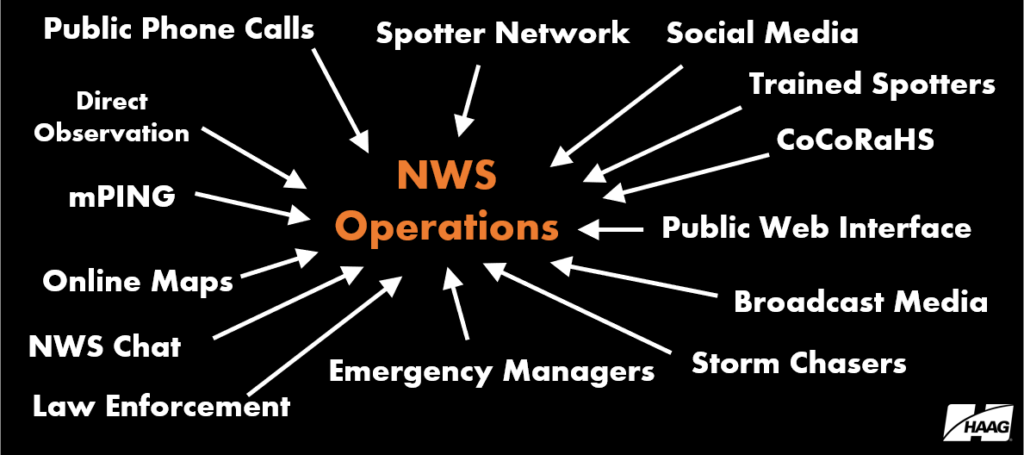

During and after any given weather event, meteorologists at the National Weather Service (NWS) Weather Forecast Offices receive reports of both severe and sub-severe weather from over a dozen different sources (Figure 1). After the weather events, each of the 122 NWS Forecast Offices review the reports before submitting them to the Storm Events Database. This quality control process usually requires 75-90 days after a weather event takes place for the official, published reports to become publicly available.

However, the details of a meteorological event can, at times, be painted with information not found in the Storm Events Database. Given the influx of reports from so many sources, it’s very easy for some of these reports to go unnoticed or undocumented by the NWS. Likewise, when there are numerous reports in one area, the NWS may simply take the largest report or consolidate reports into swaths. As such, some weather reports are not included in the official database produced and maintained by the NWS. Therefore, forensic meteorologists often need to search through the available unofficial databases, along with the officially published record when reconstructing a weather event.

Storm reports that are initially received by the NWS Weather Forecast Offices are documented as Preliminary Local Storm Reports (PLSRs). PLSRs are official products from the NWS typically issued in near real-time during a weather event, and most commonly contain severe weather reports, such as hail greater than 1.00-inch, wind greater than 58 mph, and tornadoes, along with the time and location of occurrence. However, there are times that sub-severe weather is noteworthy to the partners of the NWS (e.g. broadcast media and emergency management), so PLSRs are often produced to indicate sub-severe weather reports as well. PLSRs will, at times, contain information such as heavy rainfall amounts, snow amounts, and dense fog, among other minor weather impacts. There are certainly times in the analysis of a weather event that sub-severe weather reports will help reconstruct the details of that event. In the end, the Storm Events Database is typically populated with severe weather reports, while omitting most of the sub-severe reports and minor impacts.

PLSRs that meet severe weather criteria (1.00-inch hail, 58 mph wind, and/or tornado) become available in the Storm Prediction Center (SPC) Storm Reports database in near real-time. This is useful because there is a 75–90-day lag between the severe weather event and when the storm reports from that event are officially published in the NCEI Storm Events Database. While SPC storm reports are not quality-controlled they offer perhaps the best resource for ground truth information in the time between a severe weather event and the publishing of the official reports in the Storm Events Database.

Other storm report databases contain information provided by members of the public, who are interested in participating in the collection of weather data. Meteorological Phenomena Identification Near the Ground (mPING) was established in 2012 in a joint venture with the University of Oklahoma, the National Severe Storms Laboratory, and Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorology Studies (now CIWRO). mPING was developed to allow citizens to upload real-time meteorological information, including hail and wind reports using the GPS capabilities of their smart devices and a downloadable app. Archived mPING data can be viewed using third-party radar software.

The Community Collaborative Rain, Hail, and Snow (CoCoRaHS) network was established in 1998 and contains thousands of volunteers nation-wide who submit daily precipitation, rainfall, and snowfall measurements from their places of business or residence. When severe weather moves through their area, volunteers have the capability to submit hail reports and provide comments describing the storms.

These are just a few of the publicly available sources for unofficial storm reports that forensic meteorologists may utilize when analyzing an event. While there is an element of quality control in the process of publishing the information into the Storm Events Database, the omission of reports from PLSRs, SPC Storm Reports, mPING, CoCoRaHS, or any other unofficial database does not necessarily preclude those reports from being useful in the post-event analysis. These reports, combined with sound analysis by an experienced meteorologist can help provide details into events otherwise not made possible by using solely the NCEI Storm Events Database.

In Part 2, we will show an example of how Haag Certified Consulting Meteorologists can use unofficial databases to help paint the details of a complex severe weather event by supplementing the official, published storm reports with information provided by PLSRs, mPING, and CoCoRaHS.

Author

Jared Leighton, CCM, FORENSIC Meteorologist

Jared Leighton, CCM, is a Forensic Meteorologist with Haag Engineering Co. Based near Kansas City, Jared Leighton has over 16 years of experience in meteorology. He has spent the last decade as Senior Forecaster for NOAA National Weather Service in Kansas City, Missouri, and as a General Forecaster and Meteorological Intern prior to that position.

Mr. Leighton has extensive, comprehensive experience in NWS forecast operations across multiple geographic areas, including frequent supervision of severe and winter weather watch and warning operations. He regularly conducted storm surveys, both solo and as storm survey team lead, including multiple tornadoes in Kansas and Missouri, as well as the severe weather event on September 15, 2010, in which 7.75 inch hail occurred in Wichita, Kansas (the second largest certified hailstone recorded in the US). Mr. Leighton led and participated in several research teams, resulting in five peer-reviewed formal publications as well as presentations at local, regional, and national conferences. He also organized local storm spotter training in coordination with emergency management and led the Storm Ready community preparedness program.

Mr. Leighton earned a Bachelor of Science degree in Atmospheric Science from the University of California Davis. He is an American Meteorological Society Certified Consulting Meteorologist (CCM #783).

Any opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of Haag Technical Services, Haag Engineering Co., Haag Education, or parent company, Haag Global, Inc.